Categories

Archives

None of us wants to think about the inevitable, let alone plan for it. (“What happens once the last Lord of the Rings/Hobbit movie has been made and there are no more?” No, I mean the other inevitable.)

We can’t take our mineral collections with us.

And if we don’t think about and plan for what happens to our mineral collections, we doom ourselves to losing the pleasure of knowing we have contributed our minerals on to the next person in Mineral World. In fact, we leave open the real possibility that they may be destroyed, lost, or of no value to anyone – and any achievement in assembling our collection may be forgotten or lost too. To do that could be to let down ourselves, our families, our friends and colleagues in minerals, institutions working to preserve and promote minerals, and in many cases even the science of mineralogy. Yikes. That’s heavier than most boulders we have all contemplated dragging home with us. But true.

This topic is super tough. Why?

Well, for many of us, our mineral collections are a love, a source of happiness, a connection to nature, a pursuit involving friends, community, adventure, a basis for a feeling of accomplishment – we just don’t want to think about any of that ending. (Which as you’ll see, is perhaps not the way to think of it anyway).

But there is another major reason this is so tough to write about: there are many competing financial interests out there. From institutions, dealers and collectors to heirs, there can be a lot of money (or, more to the point, at least the perception of a lot of money) riding on this subject. Any opinion piece could offend any of their interests.

And yet… if we don’t think about it, write about it and talk about it, the minerals are often simply lost (and then, by the way, there is no money at all). And unless we actually take the bull by the horns, we can be sure that whatever we might have wanted to happen will not.

Have you ever wonder where all the thousands of great mineral specimens over the years have disappeared to, never to make another appearance in Mineral World? It’s a mineral fate we can change. And in doing so we can take real pleasure in knowing where in Mineral World our mineral specimens will go next.

Years ago, I thought it was great to hear someone take this topic on, full tilt. I mean really full tilt – a researched and well-considered approach with no particular concern about whether any potentially interested parties (collectors, institutions, dealers, or heirs) could be left raw or unhappy with any of the analysis. Which is truly what this subject needed – someone to canvass it broadly, crack it open and lay it bare.

Steve Chamberlain gave a presentation at the Rochester Mineralogical Symposium and it made people think and talk. The fundamental underlying concept: if you have generally only vaguely assumed a particular fate for your collection and otherwise thought of this as just a “some day” proposition (put your had up if this is you – be honest – it’s most of us!) think about it, starting now.

Steve’s own situation was unique and some might even find it daunting: he had a collection of approximately 25,000 specimens. This is not a typo. The disposition of his collection was a well-thought-out, complex, multi-step process involving many different approaches all for the one collection – possibly the most involved disposition I’ve heard of in terms of thought and effort in landing in just the right place all across the board for an extensive and amazing mineral collection. Most of us will never have occasion (or in some cases the desire, because of the time and effort) to do exactly what he did over a period of many years, but as a great success story and a great canvass of approaches, it stands alone. So I was thrilled when Steve agreed to reduce his talk to writing and post his piece here on the website:

Disposing of Your Mineral Collection

STEVEN C. CHAMBERLAIN

3140 CEC Center for Mineralogy

New York State Museum

Albany, New York 12230

sccham2@yahoo.com

This paper is loosely based on an extemporaneous lecture I delivered at the Rochester Mineralogical Symposium in 2004. Although I make reference to numerous facts throughout, it is really more of an opinion piece intended to encourage the reader to think seriously about the issues I raise herein. I want to thank my friends, the late Dr. Robert J. King, Dr. George W. Robinson, and Dr. Carl A. Francis, for their help in developing my own thinking about this critical, but difficult topic. Bob King and George Robinson each assembled major mineral collections and then disposed of them successfully in ways that were very informative. Carl Francis encouraged me, for years, to persuade someone to talk and write about this topic, and that someone turned out to be me.

I begin with the assertion, the ownership of a mineral specimen is temporary; it is more akin to a custodianship than to absolute ownership. In a culture sometimes obsessed with property rights, it may be legally true that I absolutely own the specimens in my collection; however, I believe I have an obligation to end my ownership is a manner that preserves the specimens for posterity. I’m not advocating the permanent preservation of every quartz crystal and every pyrite crystal that will ever be collected. I am suggesting that the more expertise a collector develops and prudently applies to the assembly of the collection, the more appropriate my assertion becomes. Crystallized mineral specimens are far too rare on the earth’s surface for us not to preserve and recycle them.

I hope everyone would acknowledge the basic truth of my assertion if one considers iconic specimens—those that have graced the covers of The Mineralogical Record or Rocks & Minerals or extraLapis, for example. Some of these individual specimens even have names, such as the Candelabra tourmaline (in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution) or the Alma King rhodochrosite (in the collection of the Denver Museum of Natural History). Consider where the threshold should be for preservation. I suggest that any specimen that is particularly desirable to any subgroup of collectors should be preserved.

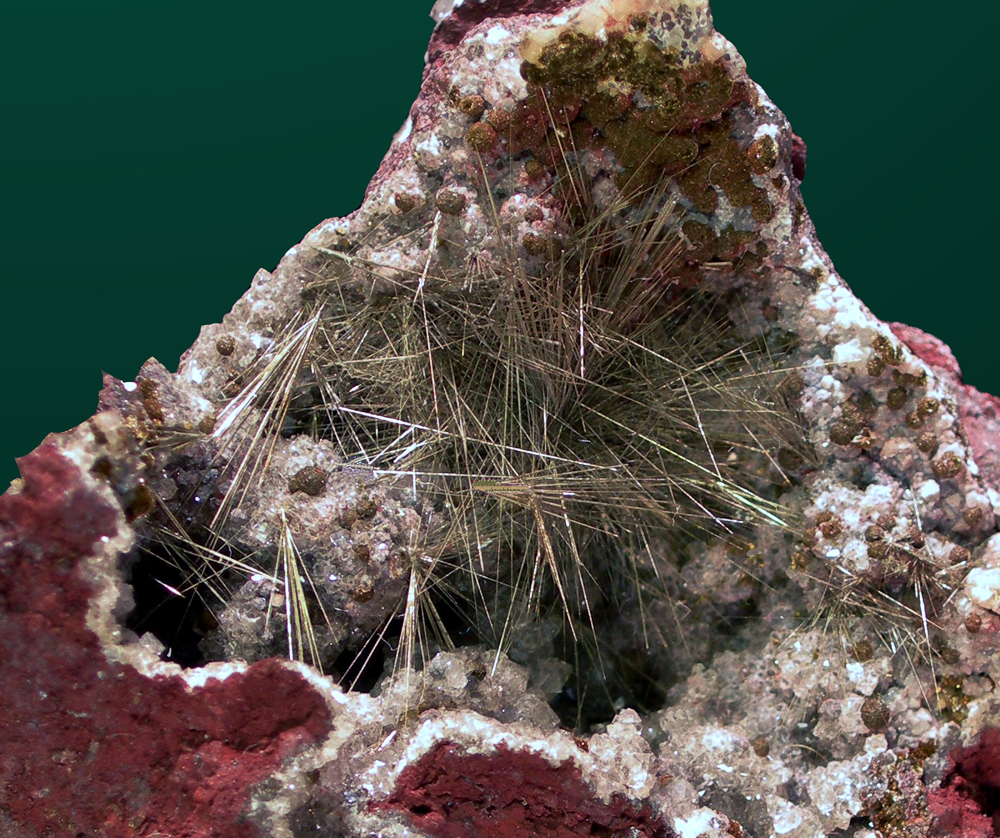

Figures 1 to 3 illustrate three specimens from my own collection that I believe ought to be preserved.

Figure 1. The Vaux millerite, from the Sterling Mine near Antwerp, NY – field of view 4.9 cm.

Originally from the Vaux collection at the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences, it is widely regarded

as one of the top several millerites ever found at this classic locality.

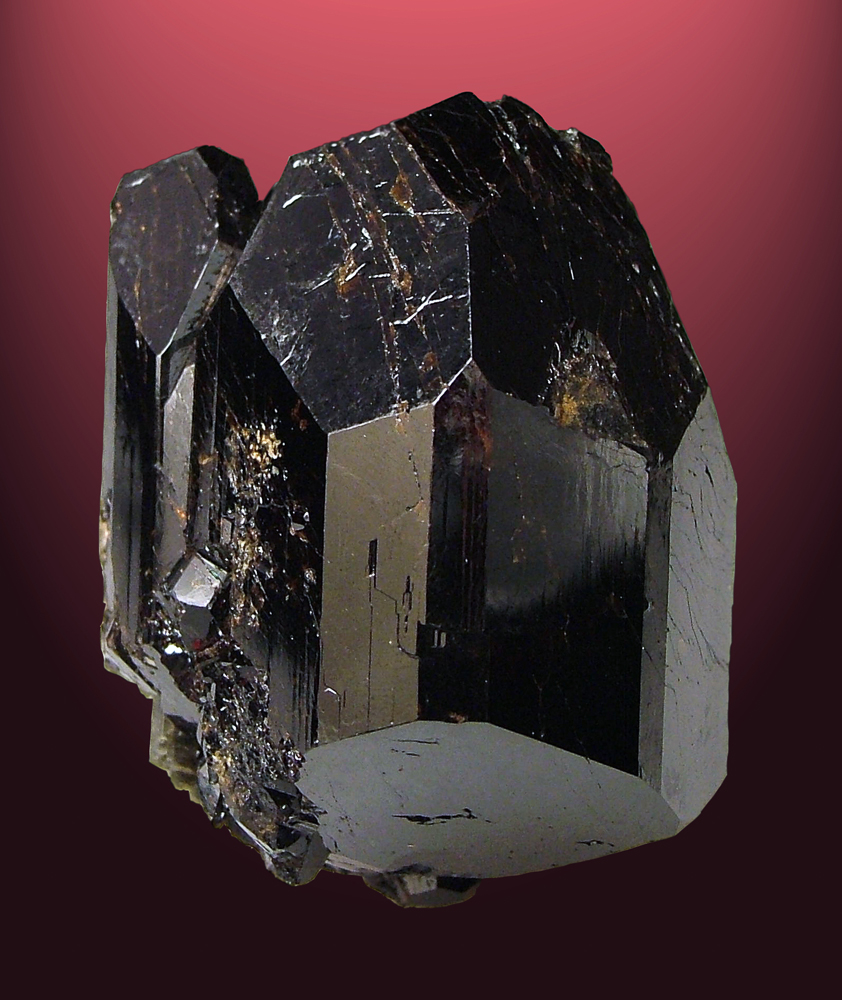

Figure 2. The Holmes fluor-uvite. This 5-cm cluster of crystals is a floater collected by Terry Holmes

at the Selleck Road locality near West Pierrepont, NY. Many regard this as the best tourmaline

ever found in NYS. The photo was taken by Michael Walter.

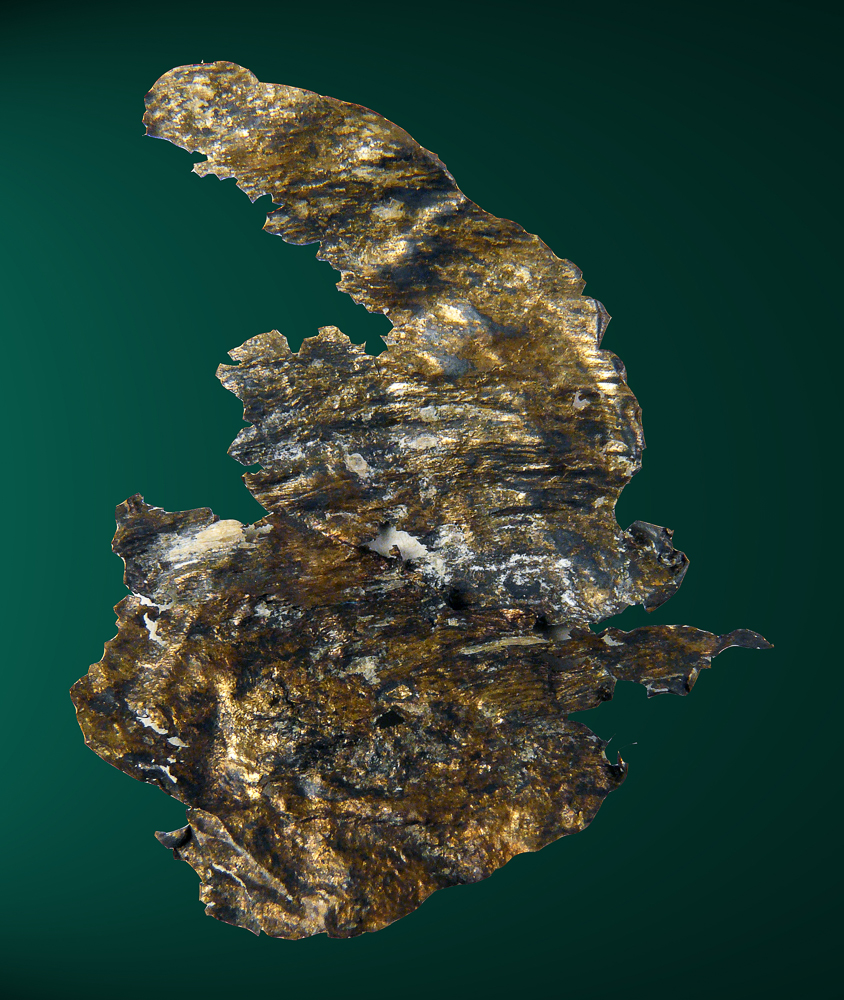

Figure 3. This 4.5-cm leaf is the only silver specimen of any size known from New York State. It was collected by mine captain Perry Caswell in the 1950s at the St. Joe #3 mine, Balmat, St. Lawrence Co, NY.

Figure 3. This 4.5-cm leaf is the only silver specimen of any size known from New York State. It was collected by mine captain Perry Caswell in the 1950s at the St. Joe #3 mine, Balmat, St. Lawrence Co, NY.

All three of these are recycled or used specimens. I am the fifth owner of the Vaux millerite, the second owner of the Holmes fluor-uvite, and the fourth owner of the Caswell silver. The desirability of used specimens with provenance is well established among collectors and is a reflection of my fundamental premise that mineral specimen ownership is temporary.

Figure 4 shows the bottom of another recycled specimen. This specimen of twinned calcite sprinkled with chalcopyrite crystals is from the Coal Hill vein near Rossie, NY. It was originally in the collection of Clarence S. Bement and went to the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). Later it was exchanged to Herb Obodda, who sold it to Dr. Ed David. Still later, it was acquired by Carter Rich, from whom I was able to obtain it. The three catalog numbers reflect residence in the AMNH, David, and Chamberlain collections.

Figure 4. Bottom of specimen of twinned calcite with chalcopyrite from the Coal Hill vein, Rossie Lead Mines, Rossie, St. Lawrence County, NY, showing the catalog numbers for collections in which this specimen has resided. Such provenance emphasizes the idea that ownership of mineral specimens is temporary.

Canfield’s Book

If you accept, at least provisionally, my basic tenet, then how does one think about and plan for the disposition of one’s own collection? Fortunately, there is a little book written by one of the most famous mineral collectors in U.S. history, Frederick A. Canfield, and privately published in 1923. (His collection was bequeathed to the Smithsonian Institution – for a brief biographical summary, click here.) This slim volume is an alphabetical record of the fate of as many mineral collections as Canfield could uncover. It is unfortunate that there is no assemblage of similar information for the years since then.

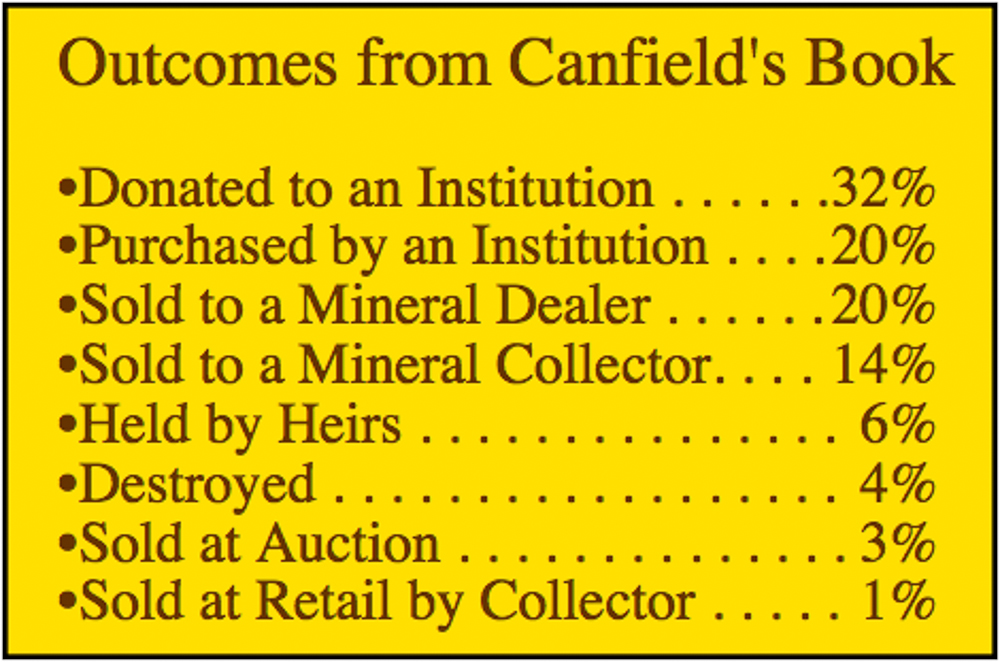

Page by page, I carefully tabulated the various mechanisms Canfield documents for disposing of mineral collections. The results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Different types of disposition of collections tabulated as percentages from Canfield’s 1923 booklet.

The disposal options have changed little in the intervening 90 years.

About half were either given to, or sold to, institutions. Another fifth were sold to mineral dealers, and a sixth were sold directly to other collectors. A few were passed on to heirs, sold at auction, or sold at retail by the collector, turned dealer. Only about 4% were destroyed. This includes the results of fires, as happened to Charles Upham Shepard’s first collection when the museum at Amherst College burned, as well as those collections that simply disappeared from knowledge.

If you ponder this tabulation, you will probably realize, as I did, that except for a few modern innovations such as internet stores and internet auctions, this is the list of mechanisms still available for disposing of mineral collections. In the next several paragraphs, I want to explore each of these in somewhat greater detail.

Donating to an Institution

I subscribe to the widely held view that important specimens and important suites of specimens ultimately should make their way to a stable museum where they will be curated and preserved in perpetuity. If you are able and willing, you can make the transfer to an institution directly. I suggest there are two major concerns to be addressed in doing this. One is financial; the other is goodness-of-match between your collection and what the chosen museum needs

In many countries, there may be a tax benefit to you if you donate your collection to a museum or other charitable institution. For example, if you are a U.S. resident, for tax purposes, if you donate all or part of your collection to an IRS-qualified institution, you can take up to 30% of your gross taxable income as a charitable deduction each year for a five-year period starting with the year of the donation. For this to yield a financial benefit, of course, you have to have reasonable taxable income, you need to secure a retail appraisal from a qualified appraiser, and you need to find someone who understands how to handle donation of mineral collections to prepare your tax returns. If you are paying income tax at the highest rate, the financial difference between selling your collection as a whole and donating it may not be very different. As the number of specimens increases, the percentage of total retail value you can expect to recover falls drastically. Since most U.S. readers will currently be paying federal income taxes at a rate between 25% and 35%, a maximum deduction can recover between 7.5% and 10.5% of the appraised retail value. Reduction on any state income tax is an added bonus. Most mineral collections are not likely to yield much more than this if sold as a lump.

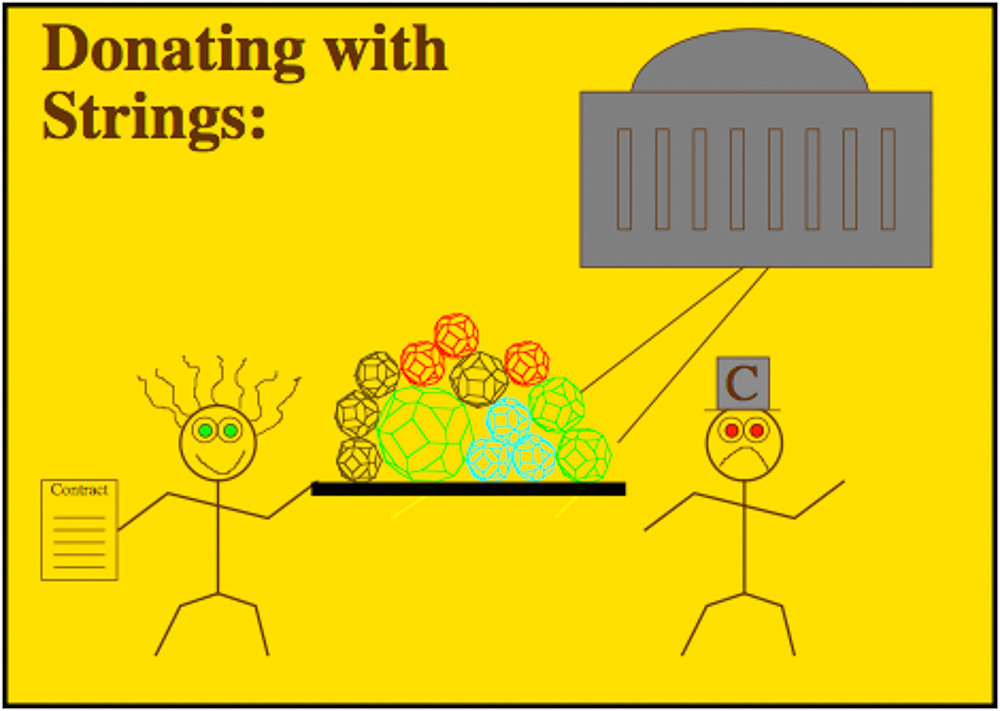

Donating to an institution with strings may initially seem like a good plan. In fact, this approach can have serious problems. Figure 6 represents such a transaction.

Figure 6. Donating to an institution with strings has disadvantages.

Note that in the cartoon, the self-focused, self-important collector on the left is pleased, but the curator on the right is not. Trying to guarantee that your collection will always be on exhibit, or that no specimens from your collection will ever leave the institution, or some other caveat, may burden the recipient institution in very undesirable ways in the future. Indeed, many curators are learning to decline donations that come with potentially expensive and toxic strings.

Now there is a not so subtle danger here. A collector who has been very focused, even ruthless, in assembling the collection may be sufficiently self-absorbed and arrogant that “no” is not an answer. If your first choice of recipient museum says no, the light should come on and you should reconsider what you are trying to do. However, some collectors may conclude that the given curator is an idiot and continue to shop around until they find a curator who is clueless enough to say “yes”. This is how the regional ornithology museum ends up with a mineral collection that they don’t know what to do with. For years I monitored a very nice collection of NYS minerals that had been donated to a local village museum because the collector lived in the village. Eventually, the important parts of the collection went to the New York State Museum, but the collection was more or less at risk for more than twenty years. I strongly suggest that you not consider donating your collection to an institution with strings. I believe there is a better approach to help assure that your donation is treated as you want it to be.

Donating to an institution without strings is, I believe, the better approach. Figure 7 represents such a transaction.

Figure 7. Donating to an institution without strings can be an excellent option.

The involved and informed collector on the left is happy and so is the curator on the right. Making a clean donation requires work in advance. You really need to understand what is in your collection. Then you need to find an institution whose holdings would significantly benefit from receiving your collection. In general this means that you ought to get to know the preexisting collection of your chosen institution and the curator should get to know your collection. Once this period of mutual discovery is well advanced, two results are likely to appear. First, there are likely to be some things in your collection that the museum really doesn’t want or need. Second, there may be certain policies, or absence of policies, at the museum that you aren’t thrilled about. The solution to the first problem is for you to segregate your collection into the portion desired by the museum, which you are eventually going to donate without strings, and the rest of your collection, which you are going to disperse in some other way. The solution to the second problem is to become involved with your chosen recipient museum as a volunteer and work on their behalf. In the process, you may well be able to address some of the things you didn’t initially like. If they need a mission statement, an acquisitions policy, a deaccessions policy, or an exhibits policy, help them to adopt such documents in writing. If they need new storage cases, offer to assist them with fund raising to acquire them. In one sense this is meritorious community service, pure and simple. In another sense, it is an investment in the future of the collection you are going to give them.

Selling to an Institution

Selling to an institution with strings is generally, I believe, delusionary baloney. Figure 8 represents such a transaction.

Figure 8. Sale to an institution with strings often leads to an unhappy ultimate outcome.

The delusionary collector on the left has his contract and is happy. The conflicted curator on the right may ultimately need a therapist. Obviously aspects of the collection are desirable enough to the institution for them to spend money to purchase it. On the other hand, it’s not a clean sale. I most strongly advise against doing this. Although the collector may rationalize that because the institution is getting the collection for a “really good price”, some strings are acceptable, nobody else, however, will see it that way. Once the collection is sold, it is sold. It belongs to the institution. The collector just has to get over any seller’s remorse associated with the sale.

Selling to an institution without strings is a nice clean way to place the collection where it belongs and reap some immediate financial benefit for doing so. Figure 9 represents this happy transaction.

Figure 9. Sale to an institution without strings can be a very good option if purchase funds are available.

Both the collector on the left and the curator on the right are happy. If the price paid is high, the curator will eventually get over any buyer’s remorse as the new acquisitions settle in to the institution’s collection. If the price paid is low, both the curator and the collector know the sale was, in part, a donation, whether acknowledged as such or not. It is, of course, possible to divide the collection formally, selling part and donating part.

In all cases where a collector sees that the collection ends up in an institution, the concept of “strings” does not include such things as access to the collection for research, or photographs, or any other procedures that are consistent with existing museum policies. You don’t need strings to retain those kinds of visitation rights. The process is not like a divorce with a court order banning you from ever seeing your children again.

Another issue in dealing with institutions is to learn what is likely to happen in the immediate and intermediate future. The trend in museums generally seems to be sliding toward hands-on exhibits and virtually-reality examination of specimens via electronic kiosks and the like. I’ve seen children sitting happily at a kiosk to look at pictures of specimens when the actual specimens were on display a few feet away, but they never looked at the actual specimens. I think this is a temporary fad, but the collector needs to become familiar with the cutting edge that exists at the institution of choice so that what may happen after the disposition of the collection while the collector is still alive is not too much of a surprise.

Finally, I must caution the reader to be careful not to disappoint the curator, even inadvertently, regardless of which specific mechanism is used to move the collection to a museum. If the curator has become familiar with the collection, if particular parts of the collection have been publicly displayed, and if specimens have been figured in books and articles, then it is critical that as the collector, you determine in advance what specimens the curator is particularly excited about receiving. It is common when disposing of a mineral collection for certain specimens to be retained as keepsakes or gifts to family members and relatives. That’s absolutely fine, provided the specimens thereby retained are not the very same ones the curator is expecting to obtain for the institutional collection. If you are giving your collection to the New York State Museum, for instance, don’t give the only known large native silver (Figure 3) to your daughter as a keepsake. Give her an equally nice one from upper Michigan or Mexico or Freiberg.

Selling to a Dealer

Figure 10 represents the process of selling your collection to a dealer.

Figure 10. Sale to a dealer works best if there is a good match between the contents of the collection and what the dealer tends to sell.

The dealer on the left needs stock and sees an opportunity to make some money. The collector is happy because he has his money. Note that the stack of bills on the left is greater than the stack of bills on the right. If you are going to sell your collection to a dealer, settle on the best price you can get and then don’t think about it any more. Of course the dealer is going to sell at least some of the specimens for a higher price, otherwise, he doesn’t even recover his costs, much less make a profit. Some dealers will buy a collection, cherry pick the specimens they can most easily sell or sell with the highest mark-up and do so. The collector may find the sale prices for these specimens grotesque; however, the increase in price partly represents the value of the dealer’s expertise, experience, and networking abilities. If you buy a specimen for $10 and sell it to a dealer 20 years later for $30, and then he sells it on his web site for $300, you just cannot allow yourself to be upset. If you wanted to sell your specimen at retail, then you needed to become a mineral dealer. Moreover, the high mark-up on selected specimens helps finance the dealer’s “being stuck” with the portion of the collection he cannot easily sell, sometimes for years.

Using this mechanism is not, however, as simple as just picking a dealer and selling your collection. Just as with institutions, finding the appropriate dealer requires both that you know what you have and that you are familiar with what each dealer knows how to sell. Unless your collection is completely self-collected and you have never, ever been to a mineral show, you ought to have some sense of which dealers sell which kinds of specimens, so that you have a sense of who may value your collection most appropriately. You will see below, in the discussion of the disposition of my own collection, an indication of the approach I took with selecting dealers and selling to dealers over a period of time.

If you haven’t been paying attention, then go to a large show with the idea of characterizing the kinds of offerings each dealer has, talk to other collectors, and go back and look at your collection’s catalog to see from whom you bought the “silver-picked” specimens.

It may well be that you will want to segregate your collection into suites so that these suites better match the commercial expertise of several different dealers. If you have a very large suite of pyrite in your collection, then a dealer who specializes in pyrite might make sense as the buyer for that suite. A dealer who sells high-end gem crystals may not know how to optimize his return on your micromount collection and as a result undervalue your micromounts when offering a price. This is surely an inexact science, but it requires some data gathering and logical thinking to work well.

Selling to Another Collector

Figure 11 summarizes the process of selling the collection to another collector.

Figure 11. Sale to another collector can be ideal when funds are available and interests are well matched.

The seller on the right has his money and is happy. The buyer on the left is “over the moon” having added more and better specimens to his preexisting collection. Under optimal conditions, this can be a very satisfying way to dispose of your collection, especially if the buyer is a younger collector with whom you have shared a joint passion for your kinds of minerals. Like donating or selling to an institution, selling to another collector can be a hybrid of donation and sales depending on price and other satisfiers. In your mind it might be that you gave away certain specimens you really wanted the recipient to have and sold the rest. Obviously some of the same comments I made about dealing with institutions also apply here. If you collect only rhodochrosite specimens from countries whose names start with the letter “T” and you sell your collection to another collector with the same specialization, then the match is virtually perfect—certainly better than it will be with any institution. Another collector, however, may be a less stable repository for your collection than an institution. Clearly a dealer is probably going to sell your collection piece by piece. Another collector may sell some of it, exchange some of it, throw some of it away and so on. Just understand this so that a fine friendship isn’t jeopardized by the sale. On the other hand, if you’ve not been able to bring yourself to plan for, and execute, disposing of your collection without dispersing it, giving or selling it to a fellow, similarly-obsessed collector rescues you and buys the collection more time.

Held by Heirs

Passing on your mineral collection to heirs as part of your estate is always an option, but often not the best option. Your last will and testament ought to address the fate of your collection, at least for the period between now and when you have disposed of it. Your sudden, unexpected demise should not leave your collection an orphan. Figure 12 summarizes leaving your collection to your heirs as a good outcome—they are all smiling.

Figure 12. Passing a collection on to heirs is fine if they are mineral collectors.

Why are they smiling? If they are mineral collectors who have learned to appreciate minerals as you do, then the outcome may well be the best one. You may want to consider giving them the collection, at least in part, while you are still alive. If they are smiling because they think the collection they have inherited is really valuable and they are actually seeing dollar signs, then you should consider whether they will have the knowledge, connections, expertise, and time to convert it to cash effectively. If the purpose of bequeathing the collection to your heirs is to give them money, it may be better for you to do the leg work to convert it into cash and give them the cash. If doing so is too much work for you, why will it not be too much work for them? Remember that this option is the default result if you do nothing now. Think about that carefully. It is possible, and often desirable, to have a separate executor for your mineral collection—someone qualified to do it.

Sold at Auction

Selling things at auction has one practical benefit; it gives everyone an equal chance to acquire what they want. Figure 13 portrays disposing of a mineral collection with an auction.

Figure 13. Dispersal at auction gives everyone a chance, but assembling the audience can be difficult.

The major practical problem is assembling the group of people holding the money and looking at the specimens. Sometimes this works. Sotheby’s has done it on occasion. Sometimes it doesn’t and the collection isn’t sold and just disappears. If a collector and collection are well known, e.g. the late Jay Lininger, an auction can be effectively organized and executed. Stack’s, a rare coin specialist, has begun having mineral auctions associated with the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show when plenty of potential bidders are in one place. The internet also provides new opportunities for selling minerals by auction as discussed in the next section.

Sold by the Collector

Sometimes a mineral collector decides to change hobbies and becomes a mineral dealer. Some mineral collectors have a second career as a mineral dealer after they retire. Most collectors, however, don’t really want to be mineral dealers. Figure 14 shows a collector selling his own collection as a mineral dealer. If you don’t identify with the smiling entrepreneur, then forget this option.

Figure 14. Selling your collection at retail only works if you really want to become a mineral dealer.

The rise of the internet has given collectors other avenues to consider. Websites, including e-commerce stores, auction sites such as eBay, and social media sites such as Facebook, provide interesting potential alternatives for some collectors since these alternatives replace the requirement to do mineral shows – instead, one’s physical travel is primarily repeated trips to the post office. Internet stores and auctions are in many ways akin to the older approach of mail-order marketing. The act of physically establishing a website can be easy, as supported by the fact that there are almost one billion websites out there. On the other hand, developing and operating a website that people actually visit, and one that attracts potential buyers and effects sales, is a rather involved undertaking. Essentially it is like opening and operating a store, but the display cases and all other aspects of the store are electronic. Running a successful website is, in most cases, just a different way of becoming a mineral dealer. Doing it well enough to profitably generate money requires a significant investment of time and work (both at start-up and on an ongoing basis) and it requires capital investment for website development, equipment and marketing (so that the website has visitors). Auction sites and other internet approaches (other than establishing a website) are typically significantly less involved, and they may or may not attract potential buyers and actual sales at the prices the collector is hoping to realize. If the collector is not photography- and tech-savvy, the overhead of paying someone else to manage any aspect of internet activity can become fairly high. In any event, internet sales require the collector to identify with the smiling entrepreneur and have a long enough timeline to make back the investment and ultimately profitably effect the sales the collector wishes to make.

Disposing of a mineral collection at retail by the collector, through becoming a dealer, remains an uncommon choice.

Destroyed

Disasters of various kinds can destroy a mineral collection despite the collector’s best efforts, but these are rare events and most collectors could easily drift into paranoia trying to protect the collection from all catastrophic events. Hurricanes, floods, earthquakes, fires and the like are fortunately uncommon enough that they do not account for most collections that are destroyed. Figure 15 shows the other scenario covered by this category.

Figure 15. A mineral collection can be lost if the collector makes no provisions for its disposition.

The collector destroys the collection, usually by a failure to plan for its disposition. The collector dies, the will says nothing about the minerals, the spouse hates all the rocks, the heirs think collecting was a kind of aberration, and the collection ends up as fill in the low spot in the back yard. Admittedly we’ve all known collectors whose so-called collections probably made better land fill than anything else, but generally an orphaned collection that is thrown out is a disaster to a greater or lesser extent. Returning to my starting premise that ownership of mineral specimens is temporary, it behooves each and every collector to avoid the destruction of the collection because of failure to plan for its disposition. If you can’t or won’t take care of the disposition of your collection yourself, at least try to make certain someone else knows what to do when the time comes.

Promotion of a Collection

This topic is a two-edged sword and talking about it is a bit like talking about religion or politics. Nonetheless… Each time specimens from a collection are displayed in public, each time specimens are figured in a journal paper or magazine article or book, each time a specimen graces a book or magazine cover or appears on a show poster, and each time a collector and collection are featured in a magazine article or magazine supplement, the probability is increased that the collection will be preserved. In part this comes from more people’s knowing that the collection and its specimens exist, but in part it comes from the fact that exposure increases the appraised and actual value of a specimen. Many appraisers believe that a figured specimen doubles in value after it appears in print. But here’s the rub. If a collection is featured in a magazine supplement and then immediately offered for sale, some people focus on the negative perception that the collector is self-promoting and greedy. An alternative way to look at it is that the collector has helped insure the specimens in the collection will be desired by others and preserved. Both views may be accurate, but personally, I try to focus on the basic truth that the better known a given specimen or collection is, the more likely it is to survive current ownership, go through disposition successfully, and be preserved.

The Disposition of My Collection

The above discussion tries to raise the issue of planning for the disposition of your mineral collection and outline most of the options that are available. Personally, I always understand things a little better if there are concrete specifics. Largely for that reason, I am going to review how my own collection was built and how I am disposing of it.

About 20 years ago, when retirement was no longer over the horizon but rapidly approaching, I first seriously considered what to do with my collection. I had assembled more than 25,000 cataloged specimens. I imagine most of you will not have that many specimens to worry about, but having a collection like mine gives one the opportunity to illustrate how various disposal mechanisms may interact in a smooth and successful way.

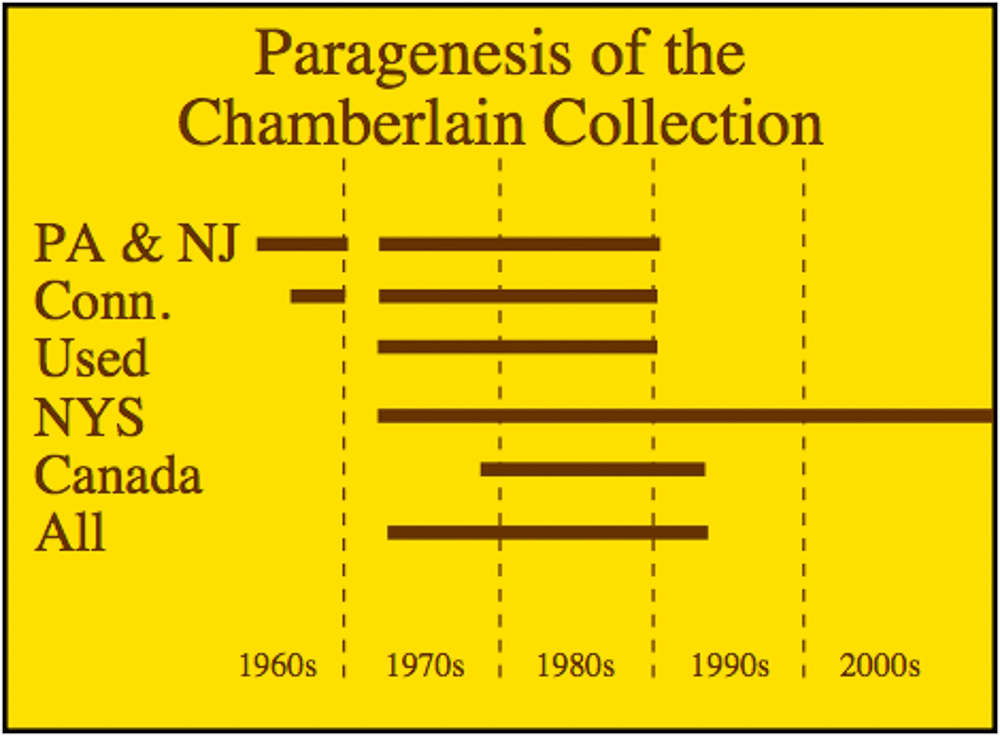

Figure 16 is analogous to a paragenesis diagram for my collection.

Figure 16. Paragenesis diagram for the assembly of the Chamberlain collection of about 25,000 specimens.

I began seriously collecting in junior high school and virtually all of my early specimens were collected personally. Since I lived in Harrisburg, PA, the early core of the collection contained specimens from Pennsylvania and adjacent New Jersey and from Connecticut because my early mentors liked to organize field trips to go there, and they took me along. The gap between 1970 and 1972 represents my time serving in the US Army, when I did no collecting. Thereafter, being married and having both a doctoral fellowship and veterans benefits, I could afford to go collecting and buy specimens, and I did. Since I now lived in Syracuse, NY, my field collecting was largely done in NYS, but still included trips to my old collecting areas in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Connecticut. I also started buying specimens that went with the things I was collecting. About this time, Ron Bentley and I became good friends, and I added old, used, and recycled specimens to my interests and really began to appreciate provenance. When Ron emptied his shop in Connecticut and moved to Tucson, I declared a financial emergency and went hog wild, adding large numbers of old specimens from world-wide localities. As my collecting in northern New York waxed vigorous apace, I began to stray into Canada, eventually finding both the Francon quarry and Mont St-Hilaire.

About 1990, I realized that my collection was threatening to spin out of control and I needed to focus. I decided to focus on the minerals of New York State, but it took me several years to curtail the acquisition of specimens from all of the other categories. By the end of the 1990s, I had actively begun to consider what was next for my collection.

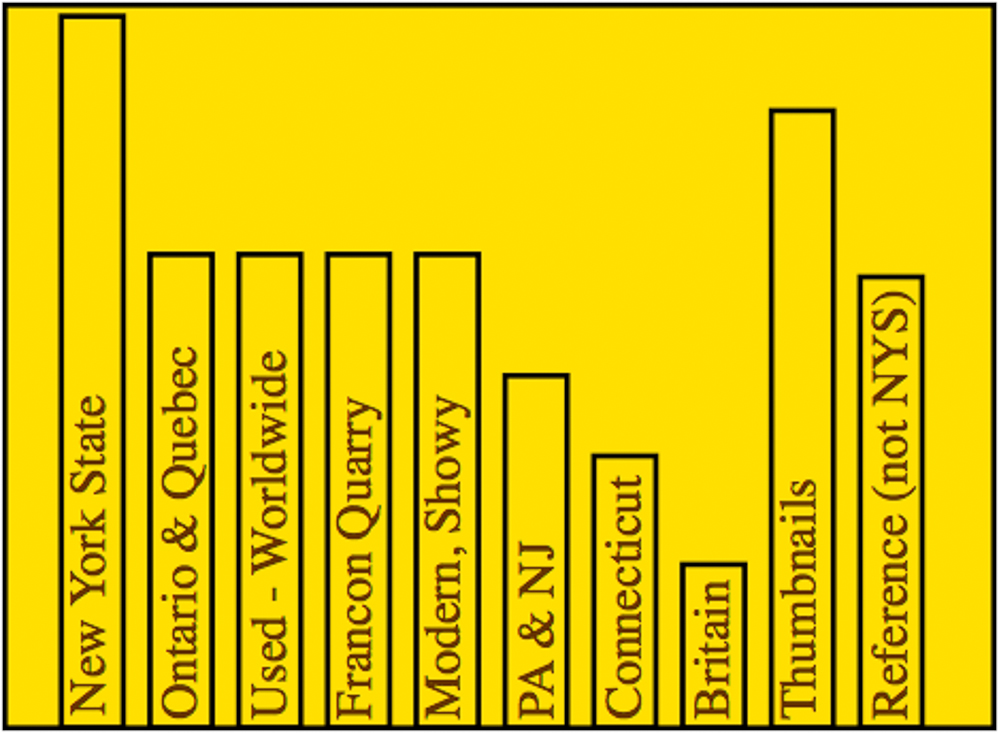

Figure 17 shows the distribution of specimens in 2000. Note that each specimen is only counted once. All NYS specimens including used specimens and thumbnail specimens are included in the first column.

Figure 17. Approximate distribution of suites in the Chamberlain collection before dispersal began.

By 2001, I had settled on the New York State Museum (NYSM) as the recipient of the NYS portion of the collection. We had organized the Center for Mineralogy and drafted and approved a mission statement and exhibits policy, and I was serving as the volunteer coordinator of the center. As I became more and more familiar both with the existing holdings of the NYSM and the political and physical environment, I decided to limit my “no strings” donation to just NYS minerals. I had two main reasons for doing that. Although the museum would probably have happily accepted everything as a donation, I concluded that burdening them with all the non-NYS specimens in my collection would create a space squeeze before I had even finished donating everything, and besides the mission statement emphasizes assembling and using a NYS mineral collection. In addition, from my perspective, the amount of work on my part to prepare, label, and catalog the non-NYS portions of the collection adequately would have been overwhelming. Just preparing labels was far easier.

As I prepared to begin donating specimens to the NYSM, the curator, Dr. Marian Lupulescu, decided that my collection should be stored and cataloged separately, resulting in two parallel NYS collections in the museum—the main collection organized by species and the Chamberlain collection organized by locality. (Note that this changed several years ago as I began to overwhelm them with specimens. Currently, the best specimens are stored with the preexisting collection, but with my numbers and catalog and the rest are stored off-site because there is just “no room for them at the inn.”) I was and am delighted with this decision, even after the recent change in approach. It permits me to assemble, study, and then donate specimens in locality suites after I am finished with any scientific work I intend to do. Moreover, it facilitates my cataloging my collection myself to avoid data entry errors that might be introduced by an intermediary. I am using the same software used by the museum, but my catalog file has a different set of fields in a different order to emphasize the topographic aspects of the collection; provenance, including figured specimen information; analysis information; crystallographic information; and collector field notes. For now, the flats for each locality are numbered sequentially so that as I find more specimens from a locality, I can just donate the next appropriately numbered flat. Each specimen has a label giving both my collection number and the NYSM collection number, as well as the mineral species, locality including GPS coordinates, and the provenance. If the specimen has been figured, a separate label giving those details is included. Of course, all preexisting labels are included and each has the catalog number written on the back side. Since many NYS localities are old prospects, a given locality may have a plethora of names. In cataloging and preparing labels, I have chosen a standard locality name. A separate locality document contains the information about synonymous names. I should mention that many of my used NYS specimens have interesting old labels. In many cases, I have given the Mineralogical Record Label Archive the original and substituted a color xerox on acid-free paper to go with the specimen (you can read more about the Mineralogical Record Label Archive here). The NYSM is very interested in the information, but an acid-free facsimile is perhaps more practical than the original label. For those specimens that went to dealers, the original labels went with the specimens, except for the occasional reference specimen with a really unusual old label. All of the old labels for thumbnail specimens mounted in perky boxes went to the MR archive. As I write this, I have donated about 10,000 specimens to the NYSM, so I have been speeding up the process.

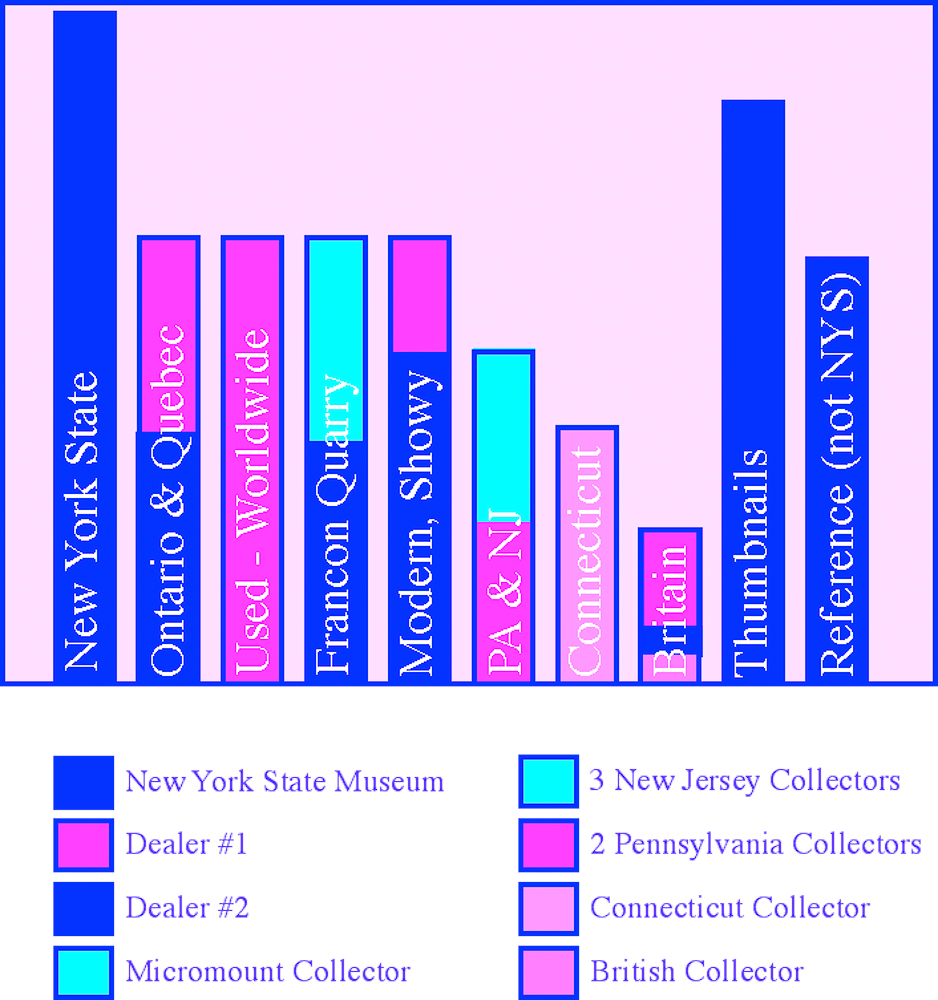

The rest of the collection was dispersed to other collectors and dealers. Figure 18 summarizes this complex process.

Figure 18. Diagram showing the relatively complex, but successful, disposition of the Chamberlain collection.

In general, I was looking for an arrangement with each dealer or collector that involved my preparing and shipping the specimens and not getting any of them back. If my starting prices were too high, we negotiated them downward. In several cases, I got unexpected credits when a dealer sold a specimen for very much more than we originally thought and he split the additional profit with me! In one case, I agreed to give two Pennsylvania specialists the opportunity to cherry pick through many flats of Pennsylvania specimens. As I had hoped, they took all the self-collected specimens from very unusual localities. Otherwise, I stuck to my plan of not becoming a dealer and not wanting any of my specimens back once they left. Several specialist collectors took a while to understand that my priority was 100% disposing of my collection and 0% pleasing them by offering them specimens that they would like for their potential purchase.

All of the dealers and collectors to whom I dispersed non-NYS specimens were old friends. I started with one dealer who had started as a micromount dealer and evolved into handling a lot of old classics with provenance. To him went the top end of the Ontario and Quebec suite and virtually all of the used specimens. Some of the modern, showy display pieces and about half of the British suite also went his way. He has now retired and his unsold stock was mostly picked up by a younger dealer who is selling some of my former specimens on the internet.

The second dealer is an active field collector who welcomed the remainder of the specimens from Ontario and Quebec, the nonmicro specimens from the Francon quarry, all the non-NYS thumbnails, and the non-NYS reference specimens. He was particularly interested in what I thought were the bottom end specimens of the modern, showy sort. They were essentially all from Mexico, no longer available, and very easily sold.

As mentioned above, much of the Pennsylvania suite went to two hardcore Pennsylvania collectors and the rest went to the second dealer. The Connecticut suite went to a Connecticut collector. The New Jersey suite was mostly zeolites and went to a group of New Jersey collectors. Selected pieces from Britain went to a collector specializing in British minerals. The Francon micromounts went to a micromount collector.

All of this worked very smoothly, once I figured out who wanted what. Many of the transactions were exchanges for more NYS specimens. Some of the transactions were straight sales. I have continued to field collect and otherwise acquire NYS specimens from localities I have not yet donated, so when all the dust has settled, the NYSM is going to get close to 25,000 specimens, but they will all be from NYS.

Lessons Learned

My experience has been that disposing of your collection in a manner that will make you happy is complicated. However, the problem seems to yield to an incremental approach. Rather than organize everything at once, I did it piece-by-piece, and eventually got to the point that the only thing that was left was the NYS suite. It took me about 10 years to disperse the non-NYS specimens. Now when I encounter additional such specimens that I missed earlier, I’ve been donating them to clubs and individuals. I’ve managed to donate between 40 and 50% of the NYS specimens to the NYSM. I’ve been speeding up the process quite a bit since the non-NYS specimens are no longer a concern. I’ve already realized I’ll never use all the charitable deductions I’m accumulating, so that’s not even an issue anymore.

I have also realized that having cataloged my collection consistently and constantly for the past 40 years is an overwhelming virtue. My first serious mentor, Dr. Davis Lapham, the Pennsylvania State mineralogist, was the person who convinced me that numbers on specimens and index cards with data were as important as the specimen itself. Fortunately he made me a true believer by the time I was 16 years old, and I have never flagged or faltered in my cataloging zeal. As a result, I am able to give the NYSM one of the most complete and certainly one of the best documented NYS collections in history.

Regarding catalogs, I should mention that I have retained all the original catalog cards. This is an idea I got many years ago from Joe Peters at the American Museum of Natural History. Now, when a Chamberlain specimen turns up without all of its labels, and I get an e-mail about such and such with a catalog number, I am able to provide the provenance and restore the specimen to its rightful state. I haven’t decided what, if anything, I’ll eventually do with the original card catalog.

I am also very happy that I am making my own entries into the electronic catalog for the NYSM. This permits me to catch all kinds of errors and inconsistencies. Each time I forward a new version to Mike Hawkins along with a new donation of minerals, the whole catalog is a bit closer to perfection.

Finally

If you’ve gotten this far, you probably already understand that I think you should begin to plan for disposing of your own collection sooner rather than later. Have a default plan in place in case you are unexpectedly kidnapped by aliens. Otherwise, develop and implement a plan that moves your specimens to new ownership in a way that you will find satisfying. When I see one of my former specimens for sale at a show or on the world-wide web or in an exhibit or in a published article, it makes me feel great. Rather than feel a sense of loss, I feel a sense of accomplishment that I’ve handled the process fairly well. If you are not ready to plan for the eventual disposition of your collection, at the very least, be certain it is cataloged—that each specimen is numbered, that the data are detailed and secure, and that any older labels bear the catalog number that will associate them with the specimen. This will make planning and implementing the disposition of your collection much, much easier when the time comes.